|

|

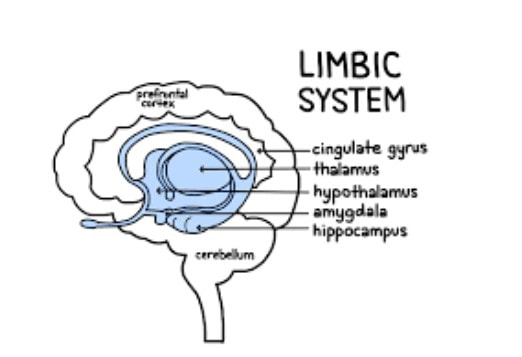

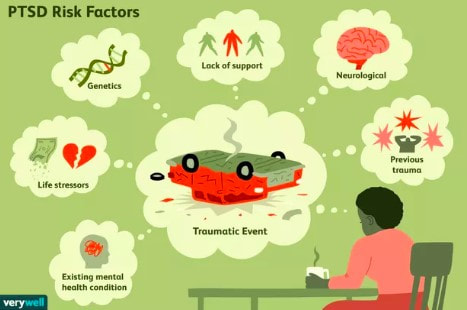

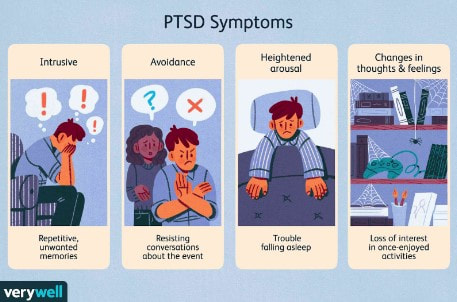

Trauma is a phenomenon that occurs when our natural coping mechanisms are unable to deal with a specific event or experience. We all have natural coping mechanisms, like emotional appraisal, social support or religion, to provide us a sense of control and safety under stressful conditions. However, certain events are so overwhelming that our defense mechanisms fail and affect our lives even after the event (Neurobiology of trauma). These events may include serious accidents, death of a loved one, sexual assault, domestic abuse, war, torture, etc (NHS). In the majority of cases, trauma leads to temporary, acute disturbances that lead to minimal functional impairment to the life of the individual. The three main classes of symptoms include 1) intrusive recollection of exposure (flashbacks and nightmares), 2) activation (hyperarousal, increased anxiety, irritability and impulsivity), and 3) inactivation (emotional numbing, avoidance, depression). In a minority of cases, however, these effects of a traumatic experience are more long-lasting and can seriously impair daily life functions (Bisson, 2015). These cases are labeled as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD) and occur in approximately 1 in 3 individuals that have experienced trauma (NHS). Unfortunately, the exact cause of PTSD and other trauma-related disorders is unclear and highly debated. One theory is that the lasting effects of trauma are a form of defense mechanism against future similar situations. For example, emotional numbing may be a way to deal with the extreme emotional stress that comes with trauma (Fang, 2020). Hyperarousal and increased anxiety may be a way to be more prepared and aware of potentially dangerous situations. Flashbacks may be a way to remind yourself of the traumatic event so that you are better prepared if a similar event happens again (NHS). Another more neurobiology-based theory is that PTSD is a result of changes in the brain chemistry that lead to abnormal regulation of certain hormones and neurotransmitters. This, in turn, leads to abnormal levels of these hormones and neurotransmitters in the brain and may be responsible for the effects of PTSD (Sherin, 2011). The major area of the brain that is affected by PTSD and is thought to be responsible for the effects of PTSD is the limbic system. The limbic system includes the amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus. The amygdala is the “fear” center of the brain and is responsible for processing threatening or frightening stimuli such as encountering a bear in the forest or your brakes not working on the freeway. So, it makes sense that the amygdala is one of the parts of the brain most affected by trauma. Trauma response and memory are stored in the amygdala, which is why a lot of emotions are evoked when recalling a traumatic experience. The hippocampus is the memory organ of the brain and has been found to be smaller in volume in PTSD patients (Sherin, 2011). This may explain why PTSD patients have difficulty accurately recalling the exact events of a traumatic experience in the correct chronological order, a phenomenon called fragmented memory (Bedard-Gilligan, 2012). The hypothalamus is the part of the brain responsible for maintaining homeostasis and activating the fight or flight response. The hypothalamus is also believed to be affected by trauma and may explain the abnormal regulation of hormones in the brain. Another area of the brain that is linked to the effects of PTSD and is the focus of research on PTSD is the HPA (hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal) axis. The HPA axis includes the hypothalamus, anterior and posterior pituitary glands and the adrenal glands. The different organs of the HPA axis communicate with one another to ultimately facilitate the activation and release of hormones responsible for the normal stress response and homeostasis. PTSD is thought to impair the HPA axis in a way that either overexpresses or underexpresses levels of these hormones in our body (Sherin, 2011). One hormone linked to PTSD is cortisol, also known as the “stress hormone” for its role in regulating our stress response under conditions of high stress. PTSD patients have been found to have generally lower levels of cortisol, which may explain their improper stress response and reduced ability to deal with future stressful situations. Another such hormone is the thyroid hormone, which controls metabolism in our body. Two thyroid hormones, T3 and T4, have been found at increased levels in PTSD patients and may be linked to subjective anxiety in these patients (Sherin, 2011). Additionally, abnormal levels of certain neurotransmitters have also been associated with PTSD, like Norepinephrine (NE) and Serotonin. NE, which is released by the adrenal glands, is responsible for the autonomic stress response system, better known as the fight or flight response. NE causes increased blood pressure, heart rate and skin conductance under high stress conditions to prepare our bodies to cope with the stress. NE hyperactivity in PTSD patients may help explain the hyperarousal, increased anxiety and flashbacks that patients experience (Sherin, 2011). Serotonin is another key neurotransmitter that is responsible for regulating sleep, appetite, impulsivity and happiness. Decreased levels of serotonin have been found in PTSD patients, which may help explain their impulsivity, depression and suicidal tendencies. For example, MDMA, which artificially increases serotonin levels, has been found to have therapeutic potential for treating PTSD (Sherin, 2011). It is unclear whether these factors associated with PTSD are the result of trauma, or are pre-existing conditions that predispose certain individuals to PTSD after traumatic experiences. Certain genetic factors have been associated with increased susceptibility to PTSD. For example, studies have shown that PTSD-like brain structures, like reduced amygdala, may be heritable and can therefore predispose an individual to higher risk of PTSD. Another such factor is gender, where females may be more susceptible to PTSD due to their increased HPA stress response. Lastly, early developmental factors may predispose an individual to PTSD. For example, children with date violence experience have been shown to be more susceptible to PTSD in the future (Sherin, 2011). Although there are many correlating factors to trauma and trauma-related disorders, there is no clear neurobiological cause of PTSD. Future research should look into which of these factors directly leads to the symptoms we see in PTSD and what can be done to prevent trauma-related disorders. It is also important to study which factors impact resiliency and vulnerability to be able to better prepare for potentially traumatic experiences and cope with the lasting effects of trauma (Sherin, 2011). References

Bedard-Gilligan, M., & Zoellner, L. A. (2012). Dissociation and memory fragmentation in post-traumatic stress disorder: an evaluation of the dissociative encoding hypothesis. Memory (Hove, England), 20(3), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2012.655747 Bisson, J. I., Cosgrove, S., Lewis, C., & Robert, N. P. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 351, h6161. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6161 Fang, S., Chung, M. C., & Wang, Y. (2020). The impact of past trauma on psychological distress: The roles of defense mechanisms and alexithymia. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00992 Neurobiology of trauma - the sexual trauma & abuse care center. (n.d.). NHS. (n.d.). Causes - Post-traumatic stress disorder. NHS choices. Sherin, J. E., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder: The neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.31887/dcns.2011.13.2/jsherin

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|