|

|

|

Postpartum depression (PPD) refers to the onset of depressive symptoms shortly after the arrival of a newborn baby. Typically, the term is linked to mothers, as the burden of delivering a baby as well as the immense hormonal changes during pregnancy and childbirth may predispose women to depression both before and after childbirth. However, an equally pressing issue is PPD in fathers, which is often overlooked both in research and clinical screenings as fathers are not seen having as direct of a role in childbirth as mothers. A closer look into PPD in fathers is needed to fully investigate and prevent depression in new fathers (Albicker, 2019).

Studies have shown approximately 1 in 10 fathers experience PPD in the first year after a child is born. Typically, PPD was highest when the baby was 3-6 months old but can also develop insidiously over a year instead of right after childbirth. Depression was not limited to just after childbirth, as depression in fathers was also seen during pregnancy, with the highest risk being in the first trimester (Rao, 2020). The symptoms of PPD in fathers are similar to those of mothers, with a few exceptions. Fathers typically showed fewer outwardly emotional responses, like crying. However, there were also male-specific symptoms of depression, like rage, irritability, alcohol abuse, sleep disorders, violent and impulsive behavior, and withdrawal from relationships (Horsager-Boehrer, 2021). There are several risk factors for PPD in fathers. One is hormonal changes, which are associated with depressive symptoms. For example, new fathers show lower levels of testosterone, which results in lower levels of aggression and higher sensitivity to a crying baby. Although lower levels of testosterone may strengthen a father’s attachment to his child, they are also associated with depressive symptoms in men (Scharff, 2019). Low self-efficacy, or the lack of ability to succeed in any given task, was also associated with PPD in men. The locus of control was important as fathers who did not feel like they were capable of raising a baby were more predisposed to depressive symptoms (Albicker, 2019). The strongest predictor of PPD in men was the past history of depression and anxiety. For example, comorbid anxiety was often observed in men with PPD, with over 18 percent of fathers experiencing high levels of anxiety after childbirth and over 3 percent having been diagnosed with GAD and another 3 percent having been diagnosed with OCD (Scharff, 2019). Depression in the mother was also associated with higher frequency of PPD in men. Other risk factors of PPD in men included feeling disconnected from mother and baby, psychological adjustment to parenthood and sleep deprivation (Horsager-Boehrer, 2021). PPD in fathers can have an effect on the development of children. Depression in fathers is associated with less attention to babies, less frequent health visits, higher risk of behavioral problems and poor family or marital relationships (Horsager-Boehrer, 2021). Infants of depressed fathers also exhibit higher levels of stress as well as delay in psychological and emotional development (Scharff, 2019). For these reasons, research into PPD in men is essential to ensure the livelihood of the infant as well as the family as a whole. However, PPD in men is not a high priority in many clinical or research settings. PPD in women is a well-researched field, whereas little research exists for PPD in men. The limitation of current studies into PPD in men is that they only look into fathers in the first year after childbirth, but not in comparison to a matched sample of men without a newborn child. Therefore, it is hard to determine that the baby played a role in the onset of depression in these men (Albicker, 2019). In clinical settings, fathers are mostly under-diagnosed and under-treated for PPD. Often during regular well-child visits, screenings for PPD are only done for mothers. Men are also less likely to seek health care services due to feelings of masculinity, shame and stigmatization of mental illness (Albicker, 2019). Therefore, future studies must include a more comprehensive look into the risk factors and effects of PPD in men. For example, to determine if a newborn increases the chances of depression in men, it is necessary to include a study with a control group to compare new fathers with a control group of men without babies. Health care services must also increase regular screenings for new fathers and reduce the stigma around receiving mental health services in men. More research must also be done on the possible treatment methods for men with PPD, such as antidepressants, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT). References Albicker, J., Hölzel, L. P., Bengel, J., Domschke, K., Kriston, L., Schiele, M. A., & Frank, F. (2019). Prevalence, symptomatology, risk factors and healthcare services utilization regarding paternal depression in Germany: Study protocol of a controlled cross-sectional epidemiological study. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2280-7 Escriba-Aguir, V., & Artazcoz, L. (2010). Gender differences in postpartum depression: A longitudinal cohort study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 65(4), 320–326. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.085894 Horsager-Boehrer, R. (2021, August 17). 1 in 10 dads experience postpartum depression, anxiety: How to spot the signs: Your pregnancy matters: UT southwestern medical center. Your Pregnancy Matters | UT Southwestern Medical Center. Retrieved February 16, 2023, from https://utswmed.org/medblog/paternal-postpartum-depression/ Rao, W.-W., Zhu, X.-M., Zong, Q.-Q., Zhang, Q., Hall, B. J., Ungvari, G. S., & Xiang, Y.-T. (2020). Prevalence of prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers: A comprehensive meta-analysis of observational surveys. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.030 Scarff J. R. (2019). Postpartum Depression in Men. Innovations in clinical neuroscience, 16(5-6), 11–14.

0 Comments

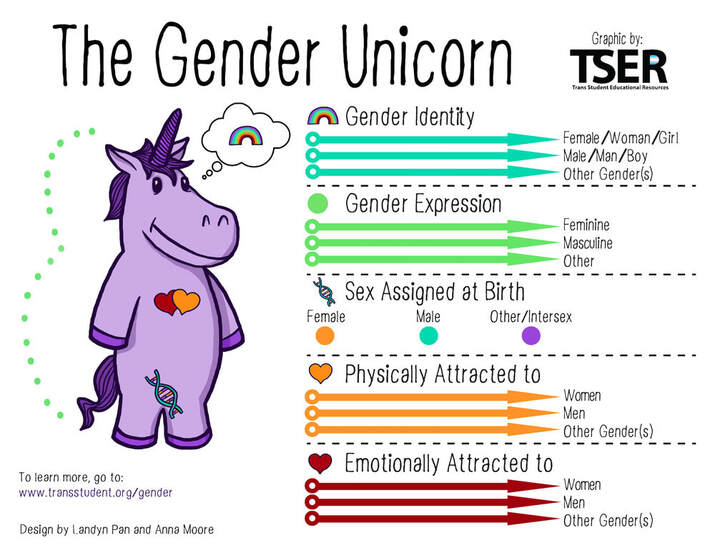

Trans Student Educational Resources (TSER) created an infographic, The Gender Unicorn, in 2014 to define the spectrums of gender and sexuality. The Gender Unicorn infographic illustrates four main concepts: gender identity, gender expression, sex assigned at birth, and attraction. Each category includes arrows to be used as sliding scales to help us recognize where we fall on each spectrum. Schools and universities often use it as a resource to help educate about gender diversity. Gender Identity: One’s internal sense of being male, female, neither of these, both, and/or other gender(s). Everyone has a gender identity, and for transgender individuals, their sex assigned at birth and their own internal sense of gender identity are not the same. Gender Expression/Presentation: This constitutes how we express or present our gender identity through clothing, hairstyles, make-up, body language, and voice. Every day, we express our thoughts and beliefs about our genders through appearance and behavior that could be classified as feminine, masculine, and/or non-conforming. Sex Assigned at Birth: The assignment and classification of people as male, female, intersex, or another sex based on a combination of anatomy, hormones, and chromosomes. (i.e AMAB - assigned male at birth) Physical Attraction: Sexual orientation. This is a part of our sexual identity that helps define our physical and sexual preferences for relationship partners. Asexuality is one sexual orientation that is used to describe someone who does not experience sexual attraction toward individuals of any gender. It is different from celibacy in that celibacy is the choice to refrain from engaging in sexual behaviors and does not comment on one’s sexual attraction. An asexual individual may choose to engage in sexual behaviors for various reasons even while not experiencing sexual attraction. Emotional Attraction: Romantic/emotional orientation. This describes an individual’s pattern of romantic attraction based on a person’s gender(s) regardless of one’s sexual orientation. For individuals who experience sexual attraction, their sexual orientation and romantic orientation are often in alignment (i.e. they experience sexual attraction toward individuals of the same gender(s) as the individuals they are interested in forming romantic relationships with). Differences between one’s sex assigned at birth and gender identity or expression may lead individuals to experience psychological distress and to be clinically diagnosed with gender dysphoria (Diamond, 2020). According to the DSM-5 TR, some transgender individuals will experience gender dysphoria, which refers to psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one’s sex assigned at birth and one’s gender identity. It can be resolved by altering one’s gender expression to coincide with gender identity, through changes in dress and appearance and, in some cases, by modifying the body through hormones or surgery. This process can be challenging, and unfortunately, gender-diverse youth have higher rates of anxiety, depression, and self-harm, and are disproportionately likely to commit suicide (Newcomb et al., 2020). By recognizing all aspects of our gender identity, we can help reduce stigma and misinformation around the conversation of gender. This is important because LGBTQ youth who live in a community that is accepting of LGBTQ people reported significantly lower rates of attempting suicide than those who do not (The Trevor Project, 2022). Resources:

References:

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|