|

|

|

Adverse childhood experiences, better known as ACEs, are traumatic experiences that an individual may experience in their childhood (0-17 years of age). For example, these experiences may include violence, abuse, neglect, witnessing a suicide attempt, growing up around substance abuse or mental health problems. The original study of ACEs came in the mid 1900s during the Kaiser study, in which participants were surveyed about their past experience with child maltreatment. The study found a correlation between childhood trauma and chronic diseases, which prompted immediate interest in the negative impact of ACEs. (Felitti, 1998). Unfortunately, ACEs are common in society, with over 61% of adults in the US having experienced at least one ACE and 1 in 6 having experienced more than four or more ACEs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022).

ACEs have been linked to several negative outcomes such as chronic health problems, mental health problems and substance abuse. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022) reported that preventing ACEs could save up to 1.9 million depression cases and 21 million depression in the US alone. In a study by Merrick et al. (2019), they found that at least five of the top leading causes of death, like respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, cancer and suicide have all been associated with ACEs. The mechanism underlying the effects of ACEs is toxic stress, which is prolonged or excessive activation of the stress response system. Although everyone experiences stress, like applying for a job, if that stress is prolonged over time or is traumatic, it can damage the body and the brain long-term, leading to mental health issues like PTSD, complex trauma, depression and substance use (Jo Hill, n.d.). ACEs have also been associated with increased risk of smoking, obesity and drug use, alcoholism and STDs. (Felitti, 1998). ACEs are commonly identified using a questionnaire that scores individuals based on the number of ACEs they’ve experienced in their childhood. Although ACEs can happen to everyone, there are some groups that are more likely to score a 1 or more on the ACEs questionnaire that can affect the individual long-term. For example, children who experience abuse or neglect are more likely to experience mental health issues and consequently abuse or neglect their own children in the future, leading to an intergenerational pattern of abuse/neglect (Jo Hill, n.d.). Women and certain minority groups were at greater risk of ACEs and may be associated with being marginalized in society. Other parental factors were associated with higher risk of ACEs, like low-income, low education status, violence, drug/alcohol abuse and single parents (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). Not only does ACE influence the individual, it also incurs costs to the families, communities and societies. A study by Peterson (2018) estimated that based on the US population cases of child maltreatment in 2015, an estimated cost of $800,000 per victim and a total lifetime burden of $428 billion are incurred annually due to the effects of ACEs. These costs include costs of health consequences, reduced quality of life and intangible costs like pain and grief. Due to the prevalence of ACEs and its impact on the lives of many, standard ACE questionnaires were made to screen for ACEs. These ACE questionnaires have been incorporated into clinical and research purposes to further examine the negative impact of ACEs. Typically in ACE questionnaires, “yes or no” type questions are asked to the respondent and the answers to these questions are scored to identify the ACEs in the individual’s childhood. However, these ACE questionnaires are not without their flaws (McLennan, 2020). For example, McLennan (2020), in his evaluation of ACE questionnaires, identifies several flaws with the most commonly used ACE questionnaire, called the ACEs-10. For one, some necessary variables of ACEs were not included in the questionnaire such as peer victimization, community violence and socioeconomic status. Second, there were problems with the construction of some of the questions in the questionnaire with some questions being potentially leading. For example, one question was preceded with the line: “Stressful life events experienced by children and teens can have a profound effect on their physical and mental health.” This information may affect the answers of the respondent as it may signal to the respondent that the clinician anticipates this relationship (McLennan, 2020). Some questions, on the other hand, were not given enough context to accurately answer the question. Lastly, a big limitation of the questionnaire was that each question was given one point and these points were summed to give an end score to determine the number of ACEs. However, this would imply that each ACE carried an equivalent weight in influencing the negative outcomes of each individual. This is obviously not true, as some experiences impact one’s life more than others (McLennan, 2020). Although no perfect method of screening for ACEs has been discovered, there exist preventive methods that may help prevent the prevalence of ACEs. It is also important for professionals who utilize the ACEs questionnaire to also consider its limitations and look at the client’s history that may also impact their presenting problems. CDC suggests that providing more financial support to families may help prevent the prevalence of ACEs in low-income families. Another method is promoting societal norms that protect against violence like education campaigns. Lastly, teaching skills like emotional learning, social skills, safe dating and parental skills may prevent the occurrence of ACEs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). If you're interested in taking a look at the ACE questionnaire or would like to see what your ACEs score is, we provided the link below: https://www.theannainstitute.org/Finding%20Your%20ACE%20Score.pdf References Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, April 6). Fast facts: Preventing adverse childhood experiences |violence prevention|injury Center|CDC. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8 McLennan, J. D., MacMillan, H. L., & Afifi, T. O. (2020). Questioning the use of adverse childhood experiences (aces) questionnaires. Child Abuse & Neglect, 101, 104331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104331 Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., Guinn, A. S., Chen, J., Klevens, J., Metzler, M., Jones, C. M., Simon, T. R., Daniel, V. M., Ottley, P., & Mercy, J. A. (2019). vital signs: estimated proportion of adult health problems attributable to adverse childhood experiences and implications for prevention — 25 states, 2015–2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(44), 999–1005. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6844e1 Peterson, C., Florence, C., & Klevens, J. (2018). The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States, 2015. Child abuse & neglect, 86, 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.09.018 Tammy Jo Hill, A. G. (n.d.). Adverse childhood experiences. Retrieved October 9, 2022, from https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/adverse-childhood-experiences-aces.aspx

0 Comments

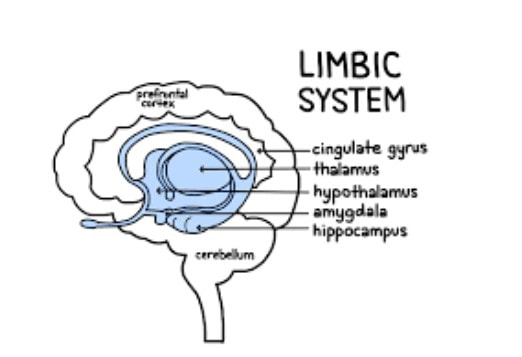

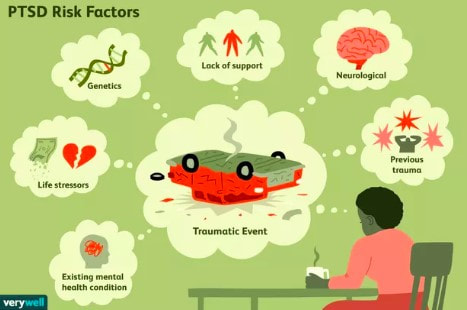

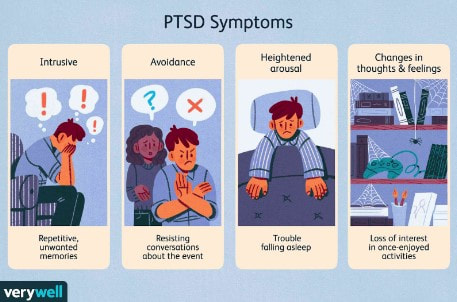

Trauma is a phenomenon that occurs when our natural coping mechanisms are unable to deal with a specific event or experience. We all have natural coping mechanisms, like emotional appraisal, social support or religion, to provide us a sense of control and safety under stressful conditions. However, certain events are so overwhelming that our defense mechanisms fail and affect our lives even after the event (Neurobiology of trauma). These events may include serious accidents, death of a loved one, sexual assault, domestic abuse, war, torture, etc (NHS). In the majority of cases, trauma leads to temporary, acute disturbances that lead to minimal functional impairment to the life of the individual. The three main classes of symptoms include 1) intrusive recollection of exposure (flashbacks and nightmares), 2) activation (hyperarousal, increased anxiety, irritability and impulsivity), and 3) inactivation (emotional numbing, avoidance, depression). In a minority of cases, however, these effects of a traumatic experience are more long-lasting and can seriously impair daily life functions (Bisson, 2015). These cases are labeled as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD) and occur in approximately 1 in 3 individuals that have experienced trauma (NHS). Unfortunately, the exact cause of PTSD and other trauma-related disorders is unclear and highly debated. One theory is that the lasting effects of trauma are a form of defense mechanism against future similar situations. For example, emotional numbing may be a way to deal with the extreme emotional stress that comes with trauma (Fang, 2020). Hyperarousal and increased anxiety may be a way to be more prepared and aware of potentially dangerous situations. Flashbacks may be a way to remind yourself of the traumatic event so that you are better prepared if a similar event happens again (NHS). Another more neurobiology-based theory is that PTSD is a result of changes in the brain chemistry that lead to abnormal regulation of certain hormones and neurotransmitters. This, in turn, leads to abnormal levels of these hormones and neurotransmitters in the brain and may be responsible for the effects of PTSD (Sherin, 2011). The major area of the brain that is affected by PTSD and is thought to be responsible for the effects of PTSD is the limbic system. The limbic system includes the amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus. The amygdala is the “fear” center of the brain and is responsible for processing threatening or frightening stimuli such as encountering a bear in the forest or your brakes not working on the freeway. So, it makes sense that the amygdala is one of the parts of the brain most affected by trauma. Trauma response and memory are stored in the amygdala, which is why a lot of emotions are evoked when recalling a traumatic experience. The hippocampus is the memory organ of the brain and has been found to be smaller in volume in PTSD patients (Sherin, 2011). This may explain why PTSD patients have difficulty accurately recalling the exact events of a traumatic experience in the correct chronological order, a phenomenon called fragmented memory (Bedard-Gilligan, 2012). The hypothalamus is the part of the brain responsible for maintaining homeostasis and activating the fight or flight response. The hypothalamus is also believed to be affected by trauma and may explain the abnormal regulation of hormones in the brain. Another area of the brain that is linked to the effects of PTSD and is the focus of research on PTSD is the HPA (hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal) axis. The HPA axis includes the hypothalamus, anterior and posterior pituitary glands and the adrenal glands. The different organs of the HPA axis communicate with one another to ultimately facilitate the activation and release of hormones responsible for the normal stress response and homeostasis. PTSD is thought to impair the HPA axis in a way that either overexpresses or underexpresses levels of these hormones in our body (Sherin, 2011). One hormone linked to PTSD is cortisol, also known as the “stress hormone” for its role in regulating our stress response under conditions of high stress. PTSD patients have been found to have generally lower levels of cortisol, which may explain their improper stress response and reduced ability to deal with future stressful situations. Another such hormone is the thyroid hormone, which controls metabolism in our body. Two thyroid hormones, T3 and T4, have been found at increased levels in PTSD patients and may be linked to subjective anxiety in these patients (Sherin, 2011). Additionally, abnormal levels of certain neurotransmitters have also been associated with PTSD, like Norepinephrine (NE) and Serotonin. NE, which is released by the adrenal glands, is responsible for the autonomic stress response system, better known as the fight or flight response. NE causes increased blood pressure, heart rate and skin conductance under high stress conditions to prepare our bodies to cope with the stress. NE hyperactivity in PTSD patients may help explain the hyperarousal, increased anxiety and flashbacks that patients experience (Sherin, 2011). Serotonin is another key neurotransmitter that is responsible for regulating sleep, appetite, impulsivity and happiness. Decreased levels of serotonin have been found in PTSD patients, which may help explain their impulsivity, depression and suicidal tendencies. For example, MDMA, which artificially increases serotonin levels, has been found to have therapeutic potential for treating PTSD (Sherin, 2011). It is unclear whether these factors associated with PTSD are the result of trauma, or are pre-existing conditions that predispose certain individuals to PTSD after traumatic experiences. Certain genetic factors have been associated with increased susceptibility to PTSD. For example, studies have shown that PTSD-like brain structures, like reduced amygdala, may be heritable and can therefore predispose an individual to higher risk of PTSD. Another such factor is gender, where females may be more susceptible to PTSD due to their increased HPA stress response. Lastly, early developmental factors may predispose an individual to PTSD. For example, children with date violence experience have been shown to be more susceptible to PTSD in the future (Sherin, 2011). Although there are many correlating factors to trauma and trauma-related disorders, there is no clear neurobiological cause of PTSD. Future research should look into which of these factors directly leads to the symptoms we see in PTSD and what can be done to prevent trauma-related disorders. It is also important to study which factors impact resiliency and vulnerability to be able to better prepare for potentially traumatic experiences and cope with the lasting effects of trauma (Sherin, 2011). References

Bedard-Gilligan, M., & Zoellner, L. A. (2012). Dissociation and memory fragmentation in post-traumatic stress disorder: an evaluation of the dissociative encoding hypothesis. Memory (Hove, England), 20(3), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2012.655747 Bisson, J. I., Cosgrove, S., Lewis, C., & Robert, N. P. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 351, h6161. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6161 Fang, S., Chung, M. C., & Wang, Y. (2020). The impact of past trauma on psychological distress: The roles of defense mechanisms and alexithymia. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00992 Neurobiology of trauma - the sexual trauma & abuse care center. (n.d.). NHS. (n.d.). Causes - Post-traumatic stress disorder. NHS choices. Sherin, J. E., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder: The neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.31887/dcns.2011.13.2/jsherin |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|