|

|

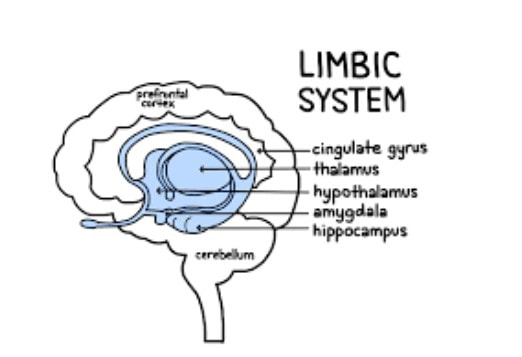

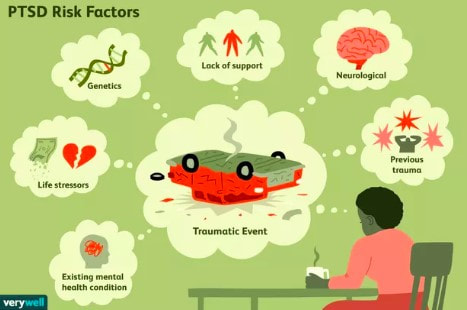

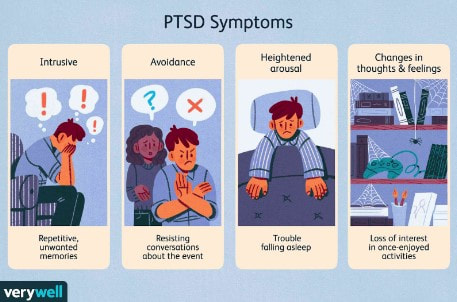

Trauma is a phenomenon that occurs when our natural coping mechanisms are unable to deal with a specific event or experience. We all have natural coping mechanisms, like emotional appraisal, social support or religion, to provide us a sense of control and safety under stressful conditions. However, certain events are so overwhelming that our defense mechanisms fail and affect our lives even after the event (Neurobiology of trauma). These events may include serious accidents, death of a loved one, sexual assault, domestic abuse, war, torture, etc (NHS). In the majority of cases, trauma leads to temporary, acute disturbances that lead to minimal functional impairment to the life of the individual. The three main classes of symptoms include 1) intrusive recollection of exposure (flashbacks and nightmares), 2) activation (hyperarousal, increased anxiety, irritability and impulsivity), and 3) inactivation (emotional numbing, avoidance, depression). In a minority of cases, however, these effects of a traumatic experience are more long-lasting and can seriously impair daily life functions (Bisson, 2015). These cases are labeled as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD) and occur in approximately 1 in 3 individuals that have experienced trauma (NHS). Unfortunately, the exact cause of PTSD and other trauma-related disorders is unclear and highly debated. One theory is that the lasting effects of trauma are a form of defense mechanism against future similar situations. For example, emotional numbing may be a way to deal with the extreme emotional stress that comes with trauma (Fang, 2020). Hyperarousal and increased anxiety may be a way to be more prepared and aware of potentially dangerous situations. Flashbacks may be a way to remind yourself of the traumatic event so that you are better prepared if a similar event happens again (NHS). Another more neurobiology-based theory is that PTSD is a result of changes in the brain chemistry that lead to abnormal regulation of certain hormones and neurotransmitters. This, in turn, leads to abnormal levels of these hormones and neurotransmitters in the brain and may be responsible for the effects of PTSD (Sherin, 2011). The major area of the brain that is affected by PTSD and is thought to be responsible for the effects of PTSD is the limbic system. The limbic system includes the amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus. The amygdala is the “fear” center of the brain and is responsible for processing threatening or frightening stimuli such as encountering a bear in the forest or your brakes not working on the freeway. So, it makes sense that the amygdala is one of the parts of the brain most affected by trauma. Trauma response and memory are stored in the amygdala, which is why a lot of emotions are evoked when recalling a traumatic experience. The hippocampus is the memory organ of the brain and has been found to be smaller in volume in PTSD patients (Sherin, 2011). This may explain why PTSD patients have difficulty accurately recalling the exact events of a traumatic experience in the correct chronological order, a phenomenon called fragmented memory (Bedard-Gilligan, 2012). The hypothalamus is the part of the brain responsible for maintaining homeostasis and activating the fight or flight response. The hypothalamus is also believed to be affected by trauma and may explain the abnormal regulation of hormones in the brain. Another area of the brain that is linked to the effects of PTSD and is the focus of research on PTSD is the HPA (hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal) axis. The HPA axis includes the hypothalamus, anterior and posterior pituitary glands and the adrenal glands. The different organs of the HPA axis communicate with one another to ultimately facilitate the activation and release of hormones responsible for the normal stress response and homeostasis. PTSD is thought to impair the HPA axis in a way that either overexpresses or underexpresses levels of these hormones in our body (Sherin, 2011). One hormone linked to PTSD is cortisol, also known as the “stress hormone” for its role in regulating our stress response under conditions of high stress. PTSD patients have been found to have generally lower levels of cortisol, which may explain their improper stress response and reduced ability to deal with future stressful situations. Another such hormone is the thyroid hormone, which controls metabolism in our body. Two thyroid hormones, T3 and T4, have been found at increased levels in PTSD patients and may be linked to subjective anxiety in these patients (Sherin, 2011). Additionally, abnormal levels of certain neurotransmitters have also been associated with PTSD, like Norepinephrine (NE) and Serotonin. NE, which is released by the adrenal glands, is responsible for the autonomic stress response system, better known as the fight or flight response. NE causes increased blood pressure, heart rate and skin conductance under high stress conditions to prepare our bodies to cope with the stress. NE hyperactivity in PTSD patients may help explain the hyperarousal, increased anxiety and flashbacks that patients experience (Sherin, 2011). Serotonin is another key neurotransmitter that is responsible for regulating sleep, appetite, impulsivity and happiness. Decreased levels of serotonin have been found in PTSD patients, which may help explain their impulsivity, depression and suicidal tendencies. For example, MDMA, which artificially increases serotonin levels, has been found to have therapeutic potential for treating PTSD (Sherin, 2011). It is unclear whether these factors associated with PTSD are the result of trauma, or are pre-existing conditions that predispose certain individuals to PTSD after traumatic experiences. Certain genetic factors have been associated with increased susceptibility to PTSD. For example, studies have shown that PTSD-like brain structures, like reduced amygdala, may be heritable and can therefore predispose an individual to higher risk of PTSD. Another such factor is gender, where females may be more susceptible to PTSD due to their increased HPA stress response. Lastly, early developmental factors may predispose an individual to PTSD. For example, children with date violence experience have been shown to be more susceptible to PTSD in the future (Sherin, 2011). Although there are many correlating factors to trauma and trauma-related disorders, there is no clear neurobiological cause of PTSD. Future research should look into which of these factors directly leads to the symptoms we see in PTSD and what can be done to prevent trauma-related disorders. It is also important to study which factors impact resiliency and vulnerability to be able to better prepare for potentially traumatic experiences and cope with the lasting effects of trauma (Sherin, 2011). References

Bedard-Gilligan, M., & Zoellner, L. A. (2012). Dissociation and memory fragmentation in post-traumatic stress disorder: an evaluation of the dissociative encoding hypothesis. Memory (Hove, England), 20(3), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2012.655747 Bisson, J. I., Cosgrove, S., Lewis, C., & Robert, N. P. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 351, h6161. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6161 Fang, S., Chung, M. C., & Wang, Y. (2020). The impact of past trauma on psychological distress: The roles of defense mechanisms and alexithymia. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00992 Neurobiology of trauma - the sexual trauma & abuse care center. (n.d.). NHS. (n.d.). Causes - Post-traumatic stress disorder. NHS choices. Sherin, J. E., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder: The neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.31887/dcns.2011.13.2/jsherin

0 Comments

An important aspect of veterans' mental health is moral injury (MI) and its impact. A moral injury can occur in response to acting or witnessing behaviors that go against an individual's values and moral beliefs. In traumatic situations, people may perpetrate, fail to prevent, or witness events that contradict deeply held moral beliefs and expectations (Norman & Maguen, 2021). Of veterans, over half have experienced moral injuries (Koenig et al., 2019). It’s often associated with a comorbidity of mental health issues such as suicide ideation and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Research has shown that moral injury is common among veterans with PTSD (Currier et al., 2019). Moral injury can accompany feelings of guilt, shame, self-condemnation, loss of trust, loss of meaning, and spiritual struggles. Veterans who experience PTSD symptoms might struggle with co-occurring cognitive, emotional, and behavioral conflicts that may have been caused by moral injuries. For some individuals, transgressing cherished moral values or experiencing betrayal by trusted others in high-stakes situations may be severely traumatic (Koenig et al., 2019). The identification and treatment of MI among those with PTSD may help in the management of symptoms. Recent research suggests that exposure to potentially morally injurious experiences may be associated with an increased risk for suicidal behavior among US combat veterans. Data from survey results were analyzed and showed that depression and PTSD were strong correlators of suicide ideation and attempts among those who experienced moral injury (Nichter et al., 2021). The events in combat and other missions may violate one’s deeply held belief systems and, for some service members, may result in inner conflict. Exposure to wartime atrocities and combat-related guilt has been shown to predict increased suicidal ideation (Bravo et al., 2020). To better inform prevention and treatment efforts among veterans, it’s important to identify risk factors that may moderate associations between moral injury and suicidal behavior. Moral injury can be self-directed or other-directed. The two categories are defined by the attribution of responsibility for the event: personal responsibility (veteran's reported distress is related to his own behavior) versus responsibility of others (veteran's distress is related to actions taken by others) (Schorr et al., 2018). In one study, self-compassion was found to combat feelings of overidentification, or a tendency to overidentify with one’s failings and shortcomings that resulted after self-directed moral injury. Mindfulness and social connectedness also were found to weaken the impact of other-directed moral injury (Kelley et al., 2019). Prayer and meditation teach individuals to bring awareness to the present moment, with a sense of nonjudgment and acceptance of current thoughts, emotions, and sensations. These may be variables that mental health professionals should consider when working with veterans who have experienced moral injuries. Some resources on moral injury include:

References

Experiencing childhood abuse or neglect is traumatic, and influences the individual’s health, relationships, brain development, and often leads to death. In 2019, 1,840 children in the United States died from abuse and neglect (National Child Abuse Coalition, n.d.). Most states regard maltreatment as physical abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2019). Maltreatment tends to take place for extended timeframes, with many individuals experiencing multiple categories of maltreatment.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are traumatic events or experiences encountered by an individual before turning 18. These incidents can include abuse, neglect, witnessing domestic violence, or having a caregiver that struggles with mental health or substance abuse. Adverse childhood experiences alter brain development, affect stress response, & increase the risk of long-term health problems, including five of the leading ten causes of death in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019). A recent study on adults in the United States found that 61% of participants experienced one adverse childhood experience, and 16% reported experiencing four or more categories (Merrick et al., 2019), exhibiting a considerable increase compared to the original adverse childhood experience study. In Felitti et al.’s (1998) study, approximately 50% of individuals reported experiencing at least one adverse experience, and 6% reported experiencing four or more. Their study also found a dose-response relationship between the number of childhood experiences and the ten top leading causes of death, which signifies that the more categories experienced by the individual, the higher their risk is for future negative health outcomes. The increasing prevalence of individuals reporting adverse childhood experiences implies that the ratio of individuals at an elevated risk for severe long-term health issues is growing. Additionally, experiencing trauma during childhood can affect the individual’s relationships with others throughout their life. Experiencing maltreatment or trauma can negatively impact attachment style, prompting them to avoid intimacy in relationships or reluctance to be close to others. Childhood abuse or observing others experience a traumatic event can prompt many individuals to develop posttraumatic stress symptoms. Children experiencing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may display changes in mood and cognition, increased physiological arousal, distress, and avoid stimuli or situations that remind them of the trauma lasting at least a month in duration (American Psychiatric Association, [APA], 2013). However, not all individuals who experience trauma will develop posttraumatic stress disorder, as an individual’s interpretation of the event also plays a role in the development. Children under six years old do not demonstrate the same exaggerated pessimistic beliefs concerning themselves, others, and the world or distorted cognitions such as self-blame that older children do (APA, 2013). Age impacts posttraumatic stress symptoms displayed partially due to differences in communication skills. Nightmares are a common posttraumatic stress symptom in children, regardless of age; however, younger children tend to reenact the events during play compared to older children (APA, 2013). Experiencing multiple categories of maltreatment may exaggerate or increase the severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Potential risk factors in caregivers that can increase the probability of abusive behavior include experiencing job loss, substance abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, having negative communication styles, or high rates of conflict (CDC, 2021). Additional social factors such as quarantines, social isolation, school closures, and low socioeconomic status increase the rate of abusive behavior (Cluver et al., 2020; Conrad-Hiebner & Byram, 2020; Peterman et al., 2020). School closures may increase abuse due to increased caregiver stress and more exposure to the abuser, with less contact with educators and other individuals likely to report abuse. Caregivers experiencing job loss during COVID-19 were five times more likely to psychologically abuse their children compared to caregivers that did not experience job loss (Lawson et al., 2020). Economic hardship or financial difficulties are positively correlated with abuse, causing individuals from lower socioeconomic status to be at an increased risk for abuse compared to other groups. This finding emphasizes the significance of implementing interventions that address the stressors associated with this life event. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) is considered one of the most effective treatments for individuals impacted by trauma in reducing posttraumatic stress symptoms (Runyon et al., 2019). This intervention can be valuable for clients that experienced a single traumatic event or multiple. The intervention often incorporates the non-offending caregiver and child when working with children that have experienced abuse, which can decrease the possibility of revictimization by enhancing parenting skills (Walker et al., 2019). Selecting interventions that supply caregivers with the resources to better cope with stressors, improve parenting skills, and relieve distress, can decrease the probability of abusive behavior occurring again. Research indicates that trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy effectively decreased internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems and improved affect regulation, self-concept, and interpersonal relationships for children that experienced sexual abuse (Hébert & Amédée, 2020). Providing children the tools to improve the harmful consequences trauma can have on self-concept, emotion regulation, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and relationships may decrease long-term consequences. Protective factors that decrease the probability of child abuse include households that focus on providing an environment where children receive the stability, support, and care needed (CDC, 2021). Caregivers with healthy communication styles, steady employment, have positive social support systems, and who can provide food, shelter, and medical care for their children are less likely to engage in abusive behavior. References

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|